This text was prepared by Institute for the History of Frankfurt

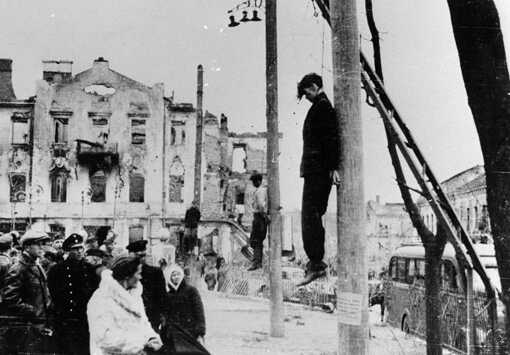

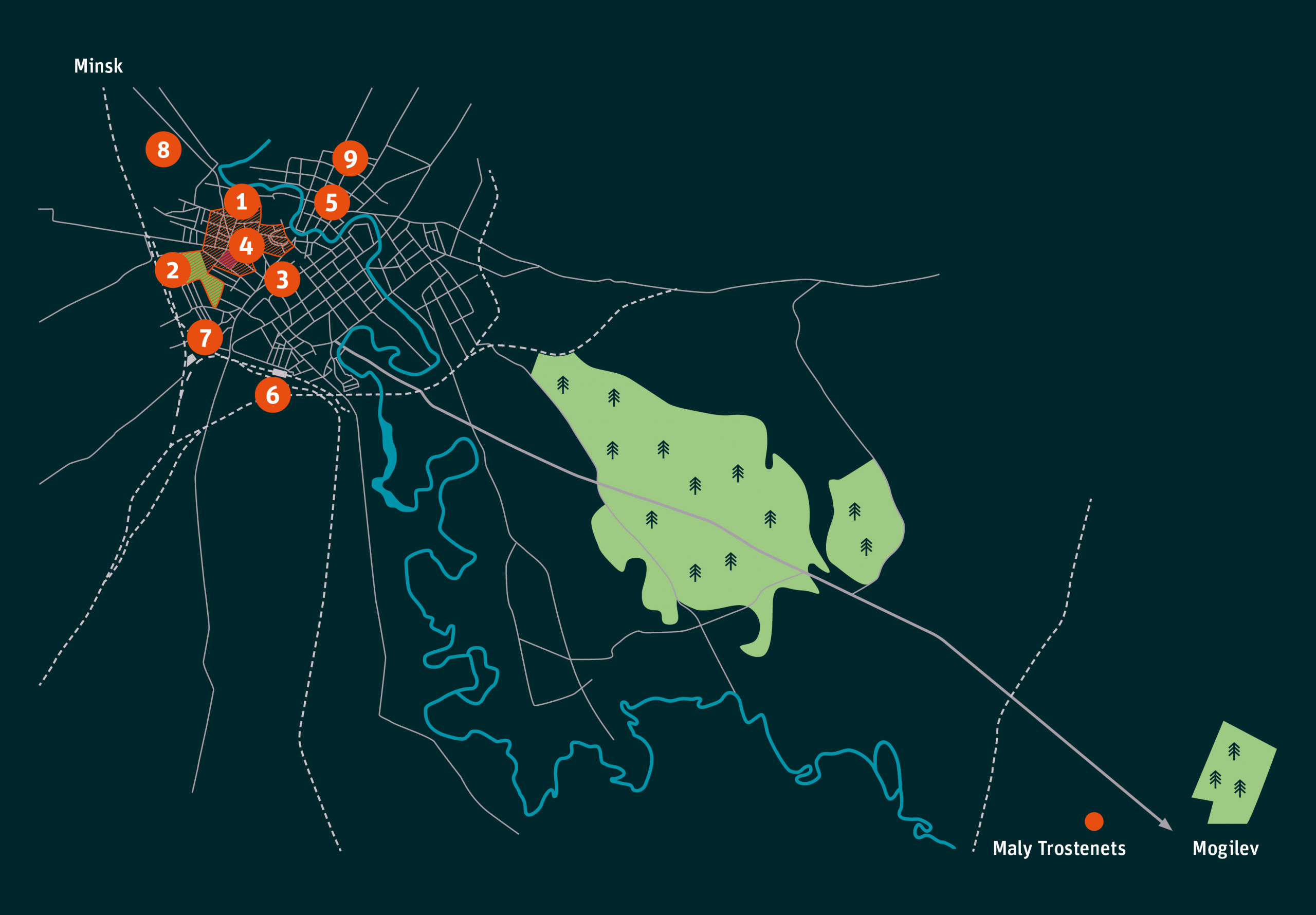

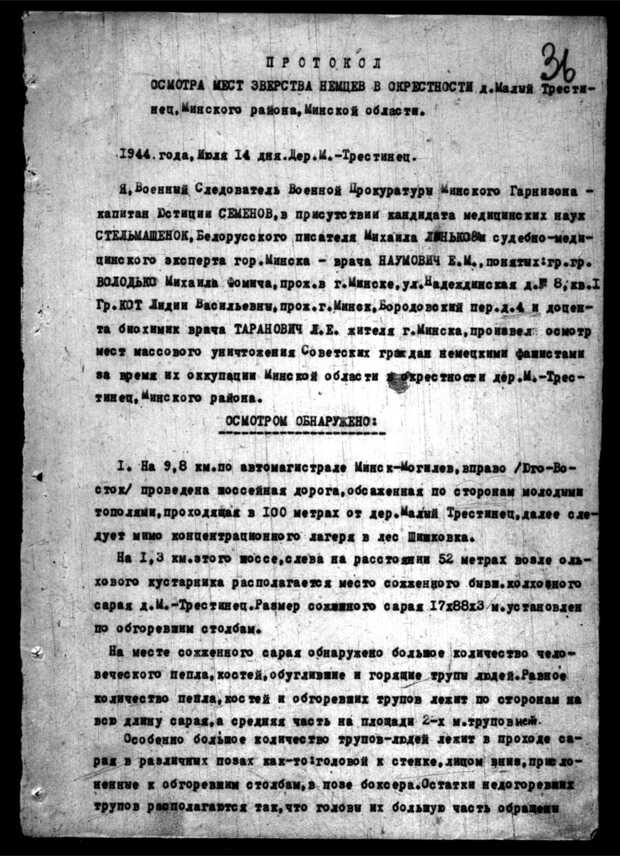

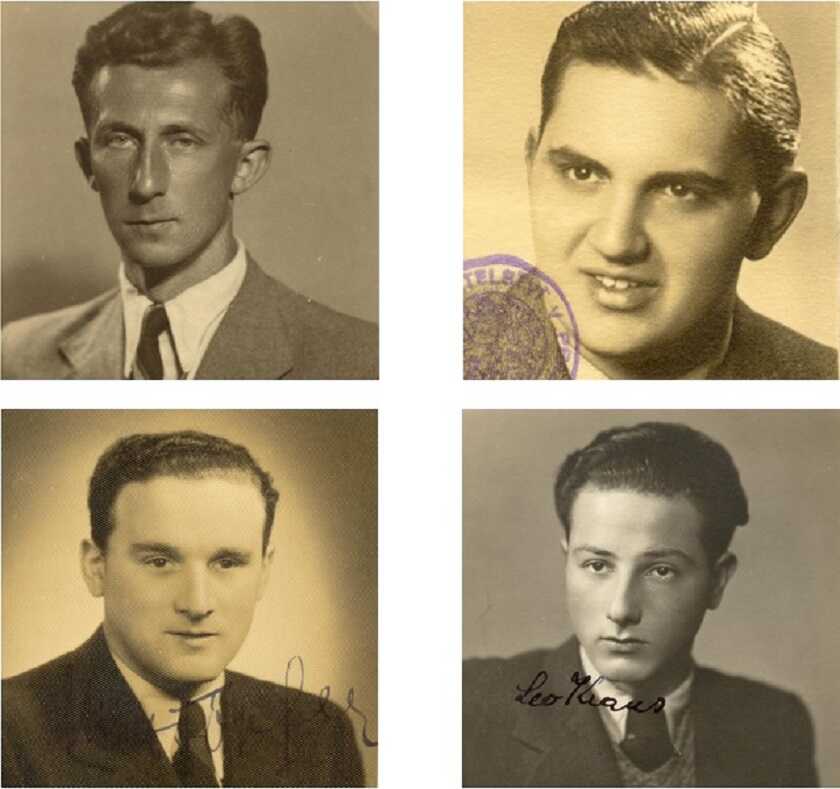

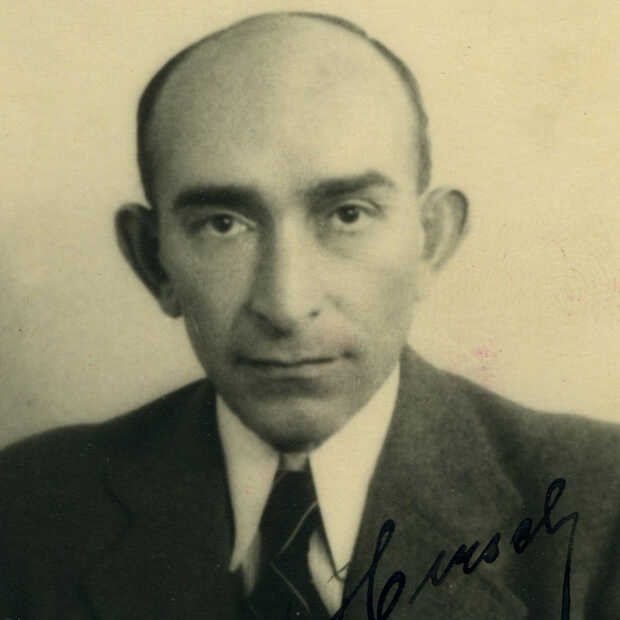

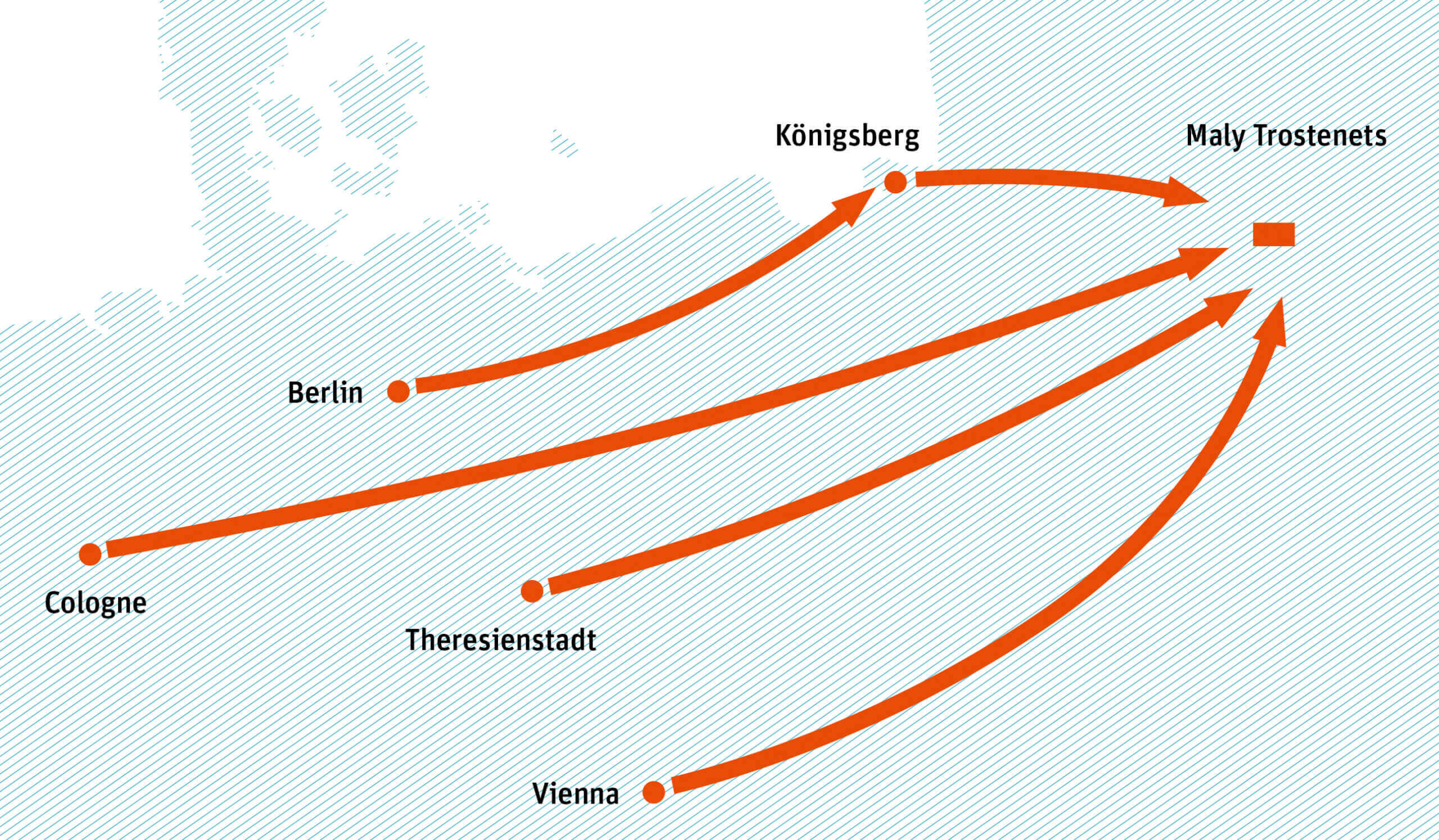

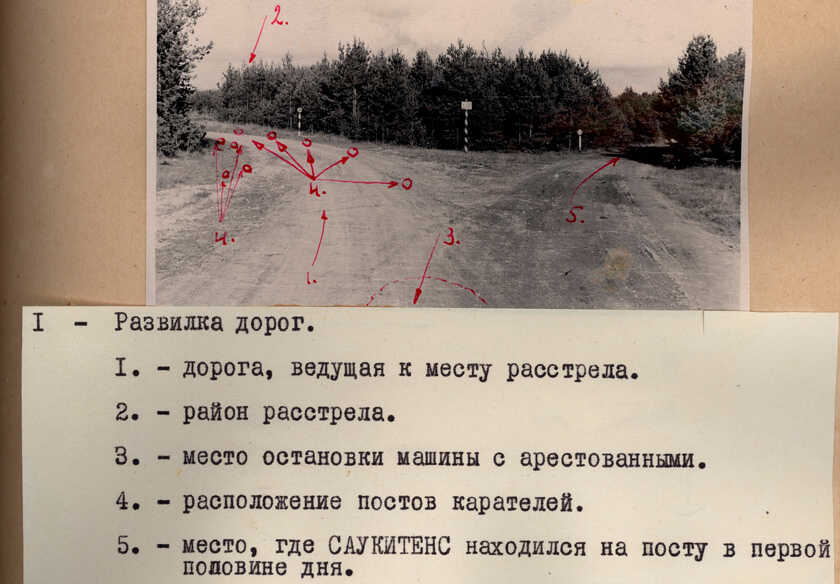

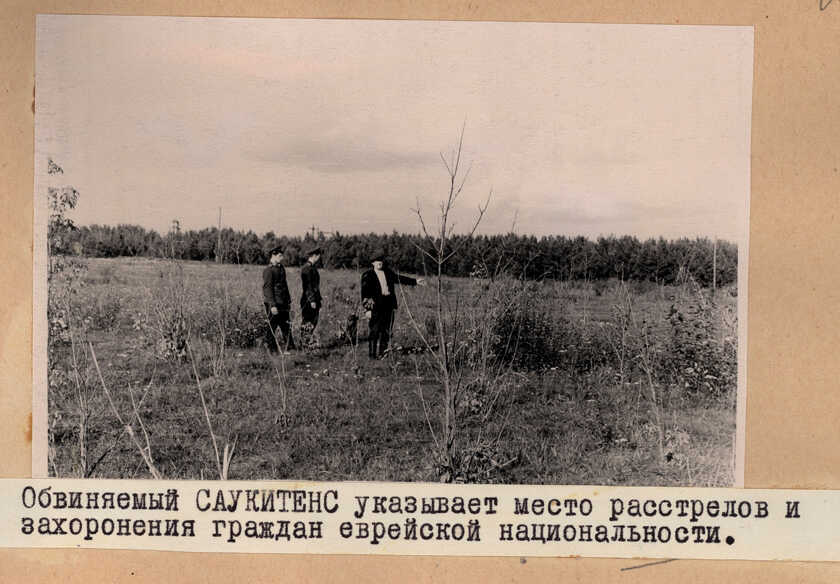

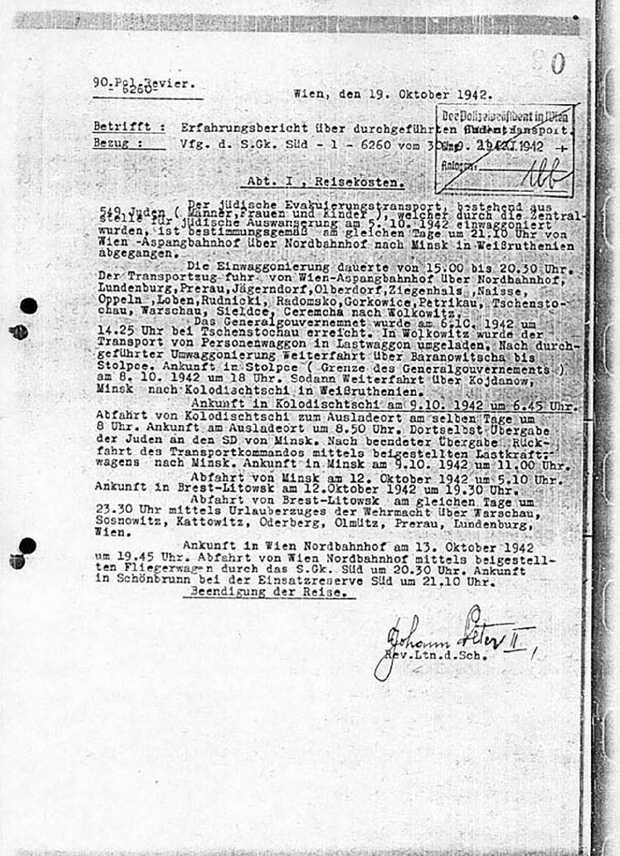

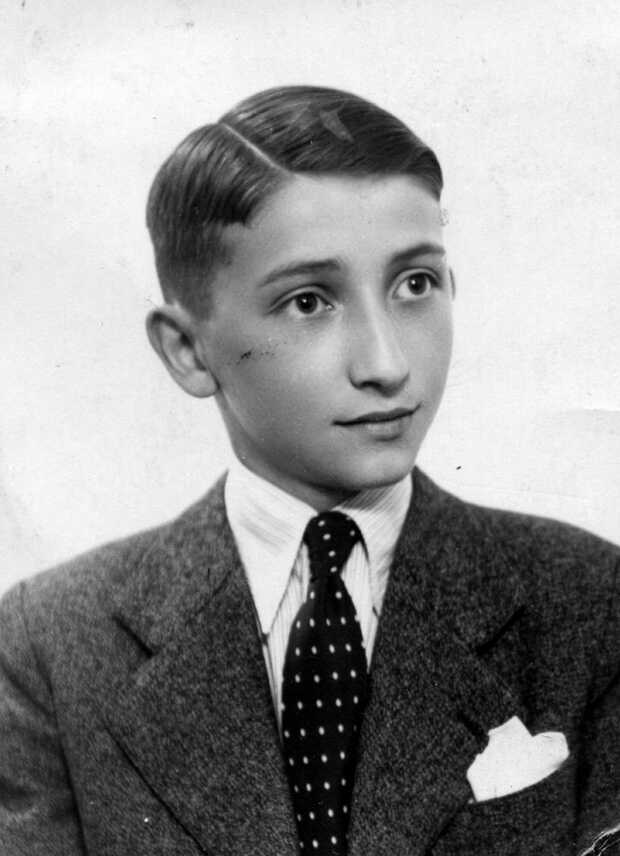

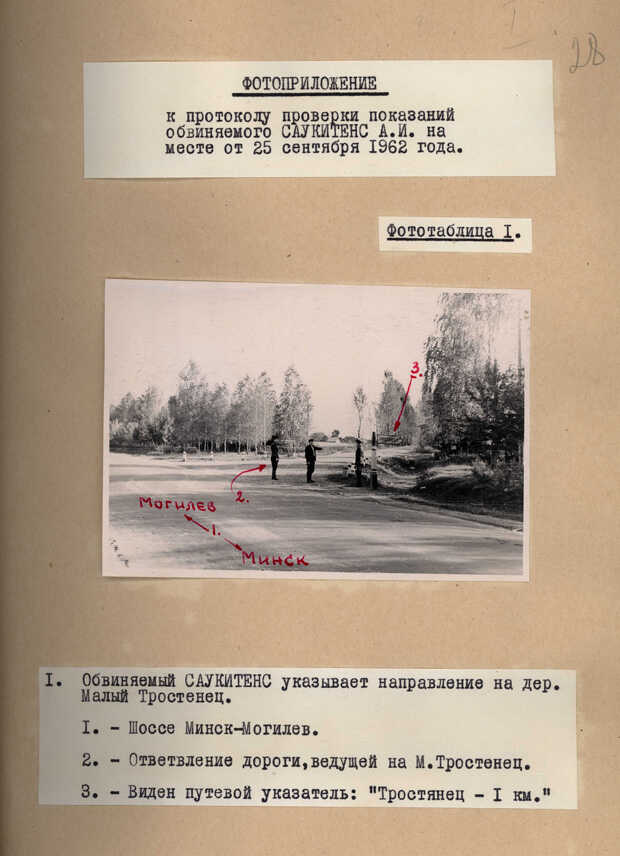

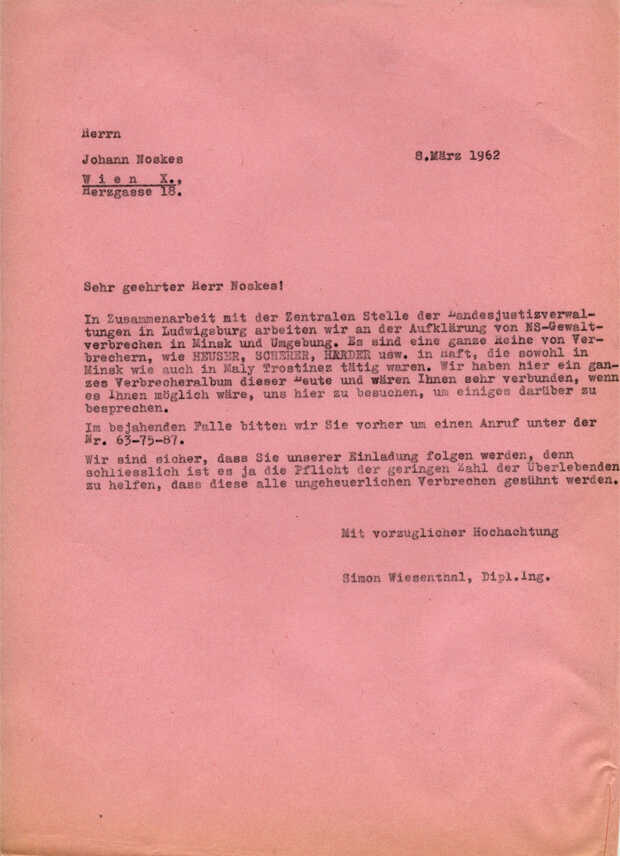

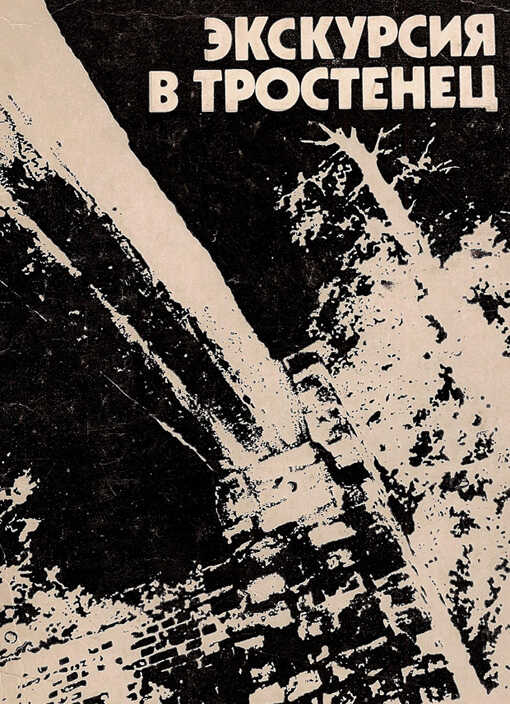

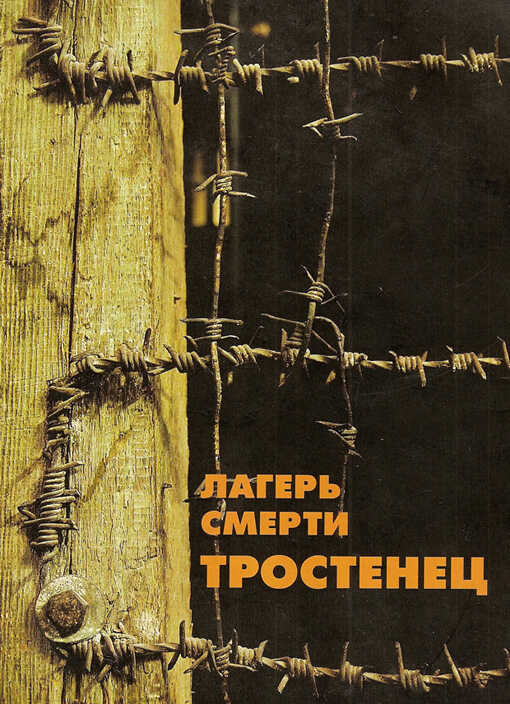

Arthur Harder was born in 1910 in Frankfurt. From September to November 1943 he headed Sonderkommando 1005-Mitte, which was responsible for removing evidence of the crimes committed in Maly Trostenets. During this period, Harder also participated in the murder of Jewish and Russian prisoners used as forced labour. In November 1943 he carried out the execution of three Jewish prisoners on the orders of the Reich Security Main Office by having them burnt alive.

Most members of the commando recalled Arthur Harder as a tall, powerful man with a loud and brutal demeanour. According to their reports, he would say, “I want to see figures!” (he used the term “figures” (Figuren) to describe the corpses as well as the prisoners) and climb on to the piles of bodies in Blagovshchina forest, and he would beat the forced labourers with whips or cudgels to get them to work faster.

After leaving school (“Volksschule”) and completing a commercial apprenticeship, Arthur Harder initially worked as an employee, but he had already joined the NSDAP and the SA in 1929 and the SS in 1930. From 1938 he worked full time for the Security Service of the Reichsführer SS. In 1942 he was called up for the Waffen-SS and was awarded the rank of Hauptsturmführer in 1944.

In May 1945 Arthur Harder was initially held captive by the British forces, who then handed him over to the Americans. As a member of the SS, he was held in Darmstadt internment camp. On 2 July 1948 a denazification tribunal categorised him as a “minor offender”, put him on probation for two years and issued him with a fine of 200 Reichsmarks.

After returning to live in Frankfurt-Eckenheim, he was a salaried employee at the Krupp vehicles firm. In the 1950s the Frankfurt public prosecutor investigated him for allegedly singing antisemitic songs during a meeting of the “Aid Association of Former SS Members” in a Frankfurt pub. During the investigations, he attacked and seriously injured a prosecution witness and was consequently given a two-month suspended sentence by a Frankfurt court.

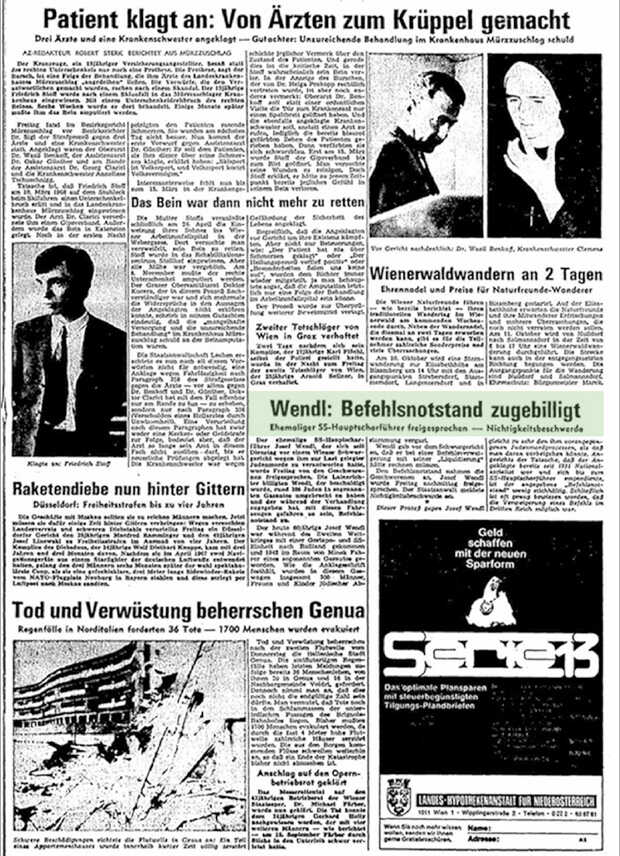

In 1963 Koblenz Regional Court found him guilty of the murder of the three Jews whom he had burnt to death in November 1943 and sentenced him to three-and-a-half years in prison. The Federal Supreme Court repealed the sentence. Arthur Harder died on 3 February 1964 in Frankfurt.