“These vans returned to the camp and we prisoners were instructed to clean them. [...] I noticed a grille in the centre of the [back] compartment, through which exhaust fumes must have come. [...] The vans were often smeared with blood, with clumps of hair, torn pieces of clothing and false teeth inside.”

Victims

Fyodor Shuvayev 1921–1989

Hanuš Münz 1910–2010

Tsyra Goldina 1902–1942

Lili Grün 1904–1942

Erich Klibansky 1900–1942

Yevgeniy Klumov 1876–1944

Nikolay Valakhanovich 1917–1989

Lea and Pinkas Rennert 1896–1942, 1894–1942

Valentina Shishlo 1936

TÄTER

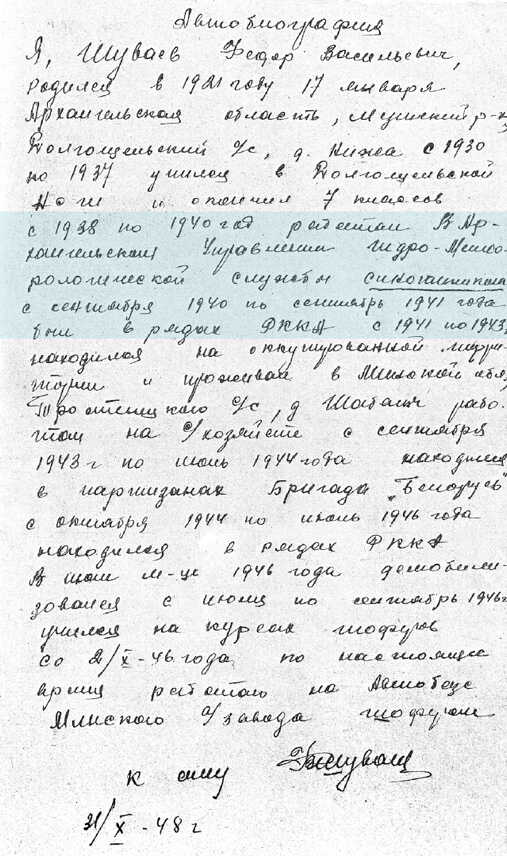

Fyodor Shuvayev

1921–1989

Fyodor Shuvayev in 1960. The photo was taken when he was interviewed as a contemporary eyewitness at the Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War in Minsk.

Belorusskiy gosudarstvennyy muzey istorii Velikoy Otechestvennoy voyny, Minsk

Fyodor Shuvayev was born in the Arkhangelsk region in the north of Russia. From 1940 he served as a soldier in the Red Army; he was stationed in Belarus at the time when the German Wehrmacht attacked the Soviet Union. In December 1941 Shuvayev was arrested near Minsk and interned in the prison in Volodarskogo Street.

At the end of April 1942, Shuvayev was brought to Maly Trostenets with around 20 other prisoners and was one of the forced labourers deployed to construct the camp. Soon afterwards he was witness to the mass murders in Blagovshchina: he had to mend items of clothing belonging to the Jews murdered there and he regularly had to clean out gas vans. In autumn 1943, he managed to escape. It was during this period that he met his future wife, Elena Shcherbach, in the village of Shabany. He joined the partisans. From October 1944 he served again in the Red Army.

After the end of the war, he remained in Minsk and worked in a car factory. Shuvayev, who had two daughters, became one of the most well-known survivors of Maly Trostenets and spoke publicly about his experiences. He died in 1989 in Minsk at the age of 68.

CV written by Shuvayev in 1948 for his job at the car factory. He made only indirect reference to his time as a prisoner at Maly Trostenets: “From 1941 to 1943 I was in the occupied territory of Minsk, lived in the settlement of Trostenets and was an agricultural labourer in the village of Shabany.”

Arkhiv Minskogo avtomobilnogo zavoda

Minsk, mid-1960s: Fyodor Shuvayev with his wife Elena (left) and their daughters Elena and Tamara.

Private collection of the Shuvayev family

Fyodor Shuvayev in 1975. The photo was taken at a school in Bolshoi Trostenets where he talked about his experience of Maly Trostenets.

Trostenezkaya Srednaya Shkola

On cleaning the gas vans

“On 9 May, the public holiday, he took me with him to the monument. There was still a small grave there. He showed me where the camp had once been [...] That was really hard for him. [...] He often spoke at schools, in Bolshoi Trostenets too. [...] Apart from on public holidays, we never spoke about this topic.”

Shuvayev ‘s daughter Elena in 2015

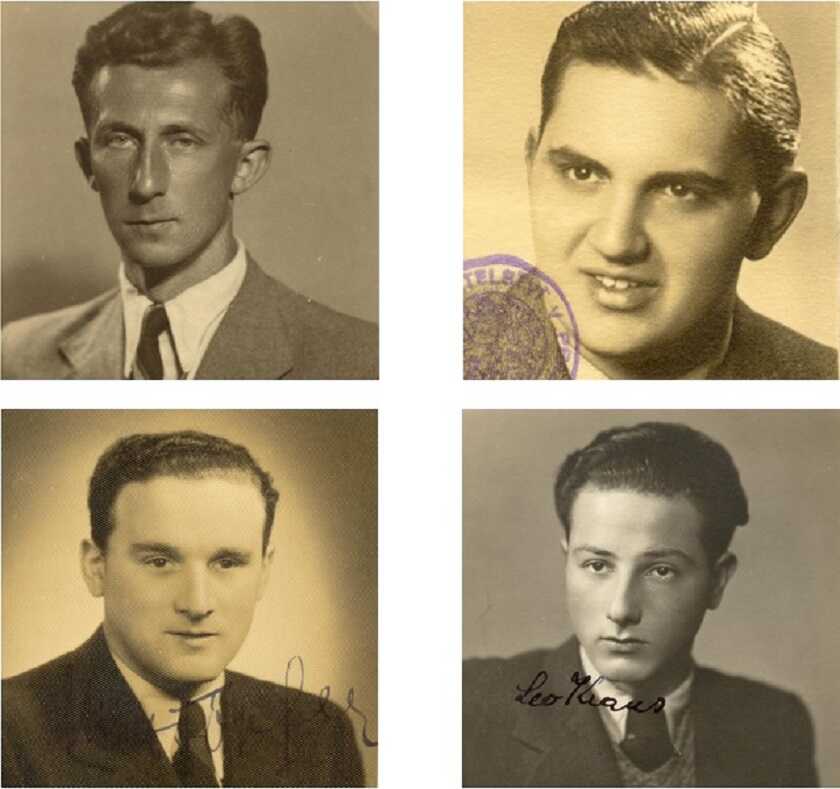

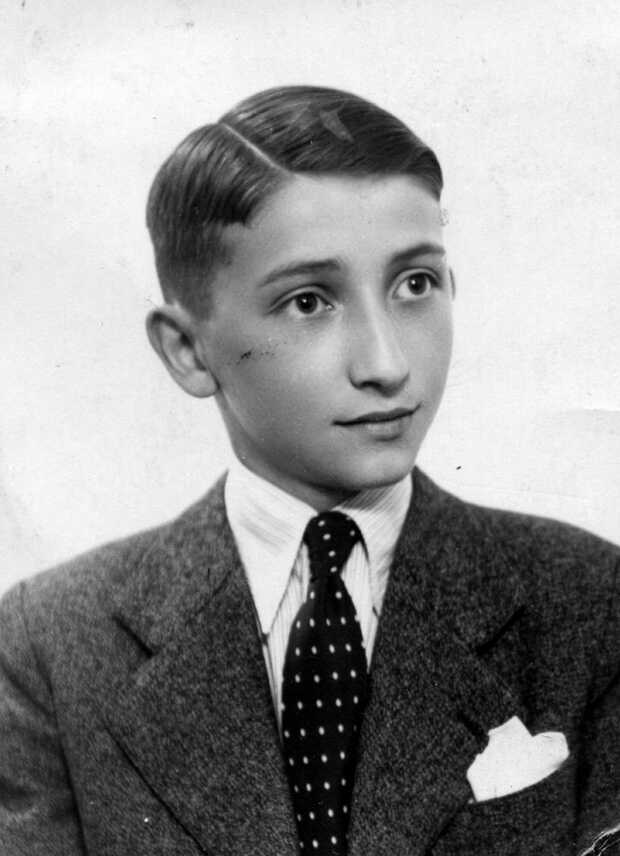

Hanuš Münz

1910–2010

Hanuš Münz at a parade in Minsk in summer 1944. After escaping from Maly Trostenets, he joined “Shturmovaya”, a Belarusian partisan brigade, and participated in numerous acts of sabotage.

Belorusskiy gosudarstvennyy muzey istorii Velikoy Otechestvennoy voyny, Minsk

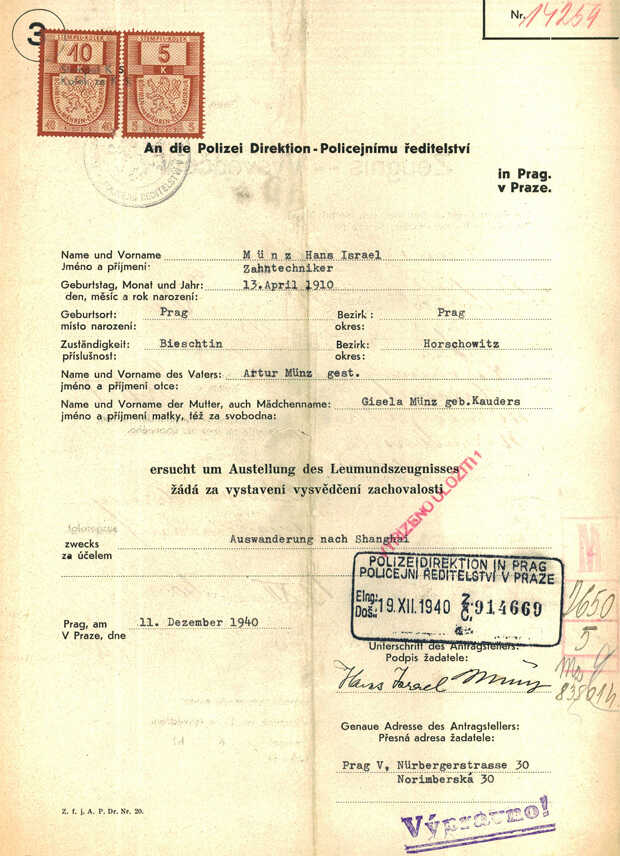

Hanuš (Hans) Münz was born in Prague in 1910; his family were Czech Jews. During the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938/39, Münz made plans to flee to Norway. In autumn 1941, he was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto and deployed in forced labour.

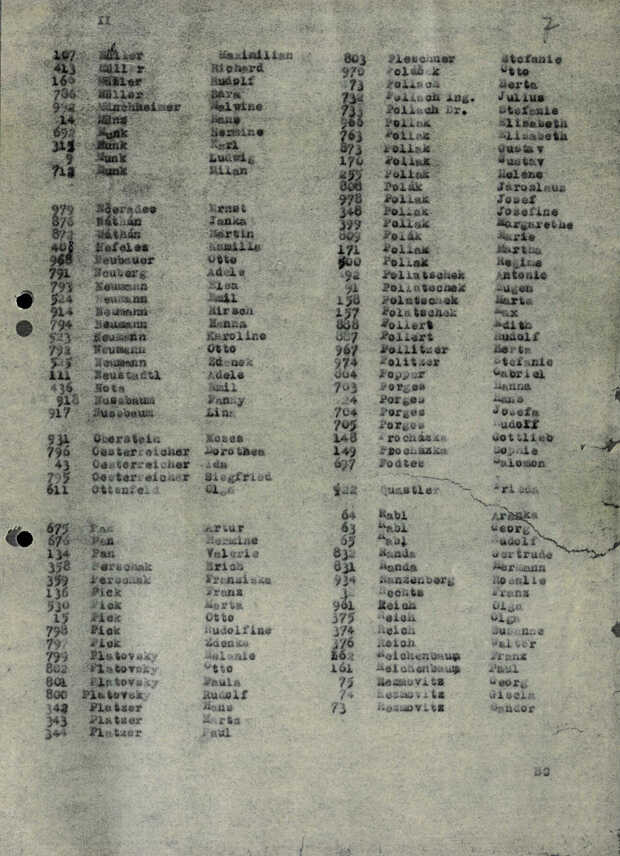

The following year, on 25 August 1942, Hanuš Münz was among a group of 1,000 Jews who were deported from Theresienstadt to Maly Trostenets. The journey took three days. On arrival, virtually all of the deportees were murdered in gas vans or shot dead in Blagovshchina forest; only 22 prisoners were selected to undertake forced labour in Maly Trostenets camp. These prisoners included Münz, who claimed to be a metalworker and was put to work in a factory in Minsk.

In 1943, Münz managed to escape. He joined the partisans and fought among their ranks until July 1944. He then served in the Red Army until the end of the war. In 1945 he returned to Czechoslovakia, where he later married and opened a dental surgery. Hanuš Münz died in 2010, shortly before his 100th birthday.

Hanuš Münz (1910–2010), Miloš Kapelusz (1920–1942), Max Töpfer (1912–1942) and Leo Kraus (1921–1944). The four men were forced labourers at a mine in Kladno and were later deported together from Theresienstadt to Maly Trostenets. Kraus and Münz were assigned to the camp as forced labourers, while Kapelusz and Töpfer were murdered in a gas van immediately after their arrival. When Münz asked a German where his friends had been taken, the answer was, “Oh, they’ve been finished off already; they’re already up in heaven.”

Národní archiv Praha, Hanuš Münz, 13.4. 1910, PŘ 1941-1950, M 2953/8; Miloš Kapelusz, 1.3. 1920, PŘ 1941-1950, K 736/4; Max Töpfer, 15.6. 1912, PŘ 1931-1940, T 342/29; Leo Kraus, 9. 10. 1921, PŘ 1931-1940, K 4302/21

In late 1940, Hanuš Münz attempted to emigrate from occupied Prague to Shanghai. However, Europe was in a state of war and he was unable to flee. Just a few months later, Münz was imprisoned in Theresienstadt.

Národní archiv Praha, Policejní ředitelství Praha – všeobecná spisovna, 1941-50, sign. H 2481/1, kart. 3294

Deportation list for the train Bc 25, 25 August 1942. Of the 1,000 Czech Jews on board, 978 were murdered immediately upon arrival at Maly Trostenets.

Národní archiv Praha, Okupační vězeňské spisy, sign. Transporty, Transport Ak Praha – Terezín, 24.11.1941.

“And so the train set off. I don’t know for how long we were travelling. At the Polish-Soviet border the train stopped, they chased us out of the carriages, and we had to get into goods wagons. […] There were 70 or 80 people in each goods wagon. We had to stand. There was no water or food. The old people suffered the most. But the worst thing was that there were no toilets. That was the worst thing of all.”

Hanuš Münz on the deportation from Theresienstadt to Maly Trostenets Židovské muzeum v Praze

“A makeshift railway station was set up for the arriving transports. We only noticed [the arrival of a new transport] when trucks full of suitcases turned up at the barn again and we […] had to sort through the contents. […] Adjacent to us in the yard was a special repair workshop for the gas vans. And when the gas vans were made ready for use again, I knew that a new transport was due to arrive.”

Münz on his time in Maly Trostenets camp Interview with Dieter Corbach, 1992

Tsyra Goldina

1902–1942

There are no surviving photos of Tsyra Goldina or her family.

Before the war, Tsyra Goldina (née Milenkaya) and her husband Efim Goldin (1906–1974) worked in the “Oktober” textile factory in Minsk. The couple had three children: Rahil (born in 1928), Lazar (1931–1982) and Aron (1936–1942). The family were of Jewish origin but did not practise their religion. They spoke Russian at home. When the war broke out, Efim was evacuated to the interior of the Soviet Union along with other factory workers. Tsyra remained behind with the children. In July she had to move with them into the ghetto, and from then on they lived at her sister Ida’s house in very cramped conditions. Tsyra’s two oldest children, Rahil and Lazar, had to undertake forced labour at a goods depot; they were at least able to barter items of clothing for food and thereby to feed the family.

On 28 July 1942 the SS and their auxiliaries forced around 10,000 ghetto residents out of their homes – a total of 6,500 local Jews and 3,500 German Jews from Sonderghetto (“special ghetto”) 2. Most of them were children, women and elderly people. They were either brought by truck to Blagovshchina, where they were shot, or they were murdered in gas vans on the way there. Their bodies were then hastily buried. The operation took three days. Among the victims were Tsyra Goldina, her five-year-old son Aron and Tsyra’s sister Ida.

Before the war, the family lived in a house with a large yard at Revolution Street 24. There are no surviving photos of this building either.

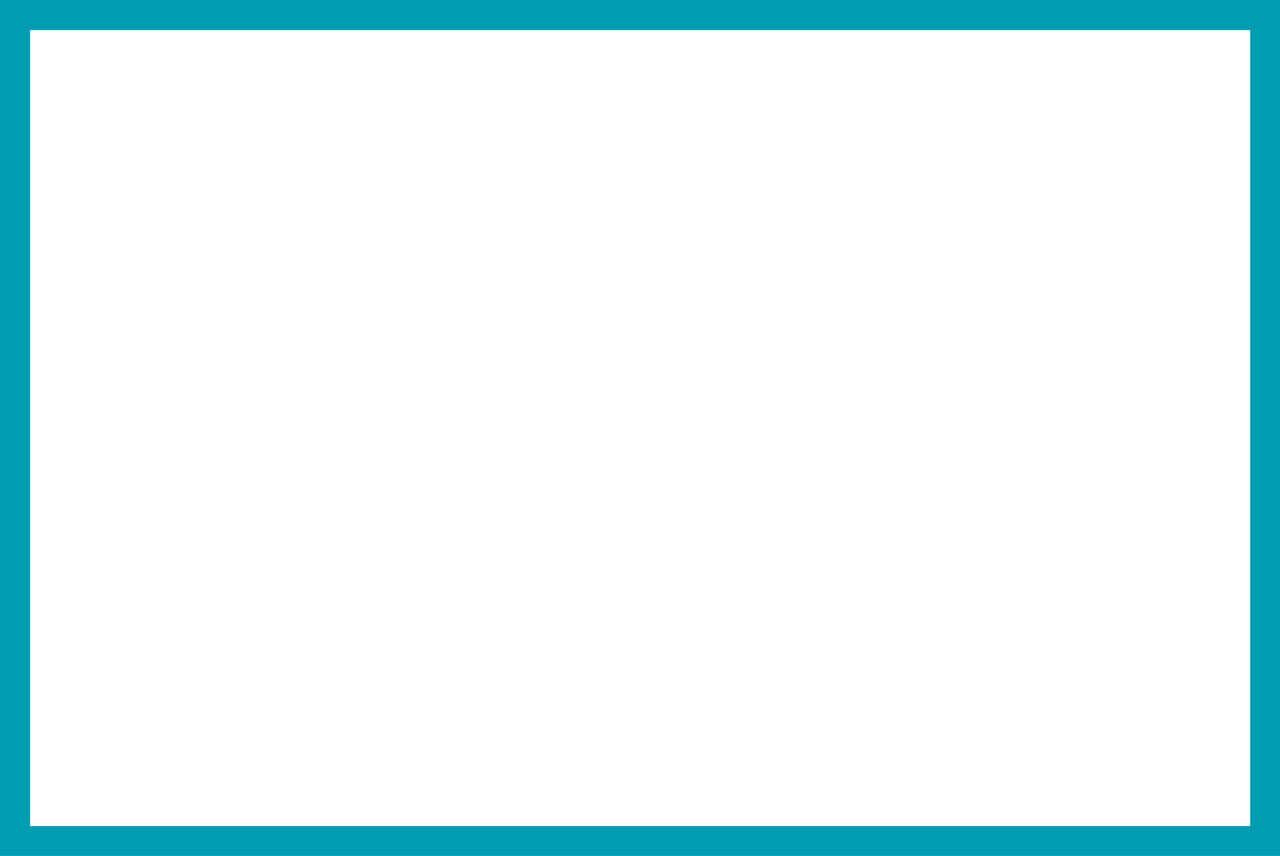

The former choral synagogue in Minsk, 1932. Following the October Revolution in 1917, heavy restrictions were placed on practising religion, including Judaism. This synagogue was at first used by the Jewish State Theatre and then converted into a cinema.

Belorusskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv kinofotofonodokumentov, Dzerzhinsk

Tsyra Goldina’s daughter, Rahil Perelman, in 1946 and 1997. She lives in New York. Her daughter Tatyana Tsukerman (born in 1949), who lives in Moscow, states:

“My mother Rahil and her brother Lazar left the ghetto every day to go and work at the railway station. One day in July 1942 they were detained at work and not allowed to go home. […] Rumours circulated immediately about a pogrom in the ghetto. When they returned to the ghetto, there was no one left. It was the largest pogrom in 1942. They were told that their mother and their brother Aron had died, that they had been taken to Trostenets. […] My mother and Lazar later attempted to join the partisans, but they were arrested on the way and put in prison in Minsk. My mother was later taken to Auschwitz.”

Shoah Foundation, Los Angeles

Tsyra Goldina’s daughter, Rahil Perelman, in 1946 and 1997. She lives in New York. Her daughter Tatyana Tsukerman (born in 1949), who lives in Moscow, states:

“My mother Rahil and her brother Lazar left the ghetto every day to go and work at the railway station. One day in July 1942 they were detained at work and not allowed to go home. […] Rumours circulated immediately about a pogrom in the ghetto. When they returned to the ghetto, there was no one left. It was the largest pogrom in 1942. They were told that their mother and their brother Aron had died, that they had been taken to Trostenets. […] My mother and Lazar later attempted to join the partisans, but they were arrested on the way and put in prison in Minsk. My mother was later taken to Auschwitz.”

Private collection of the Perelman family

Tatyana Tsukerman (left) with her second cousin Shalhevet Sara Ziv, who lives in Israel. Their grandmothers were sisters.

The recollections of her mother Rahil inspired Tatyana to work as a teacher in the field of Holocaust education. She regularly recounts her family’s story to school groups. In 2015 she took part in a seminar for teachers at Yad Vashem, Israel’s national memorial site in Jerusalem. By coincidence, she found out that she has relatives living in Israel.

Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

Lili Grün

1904–1942

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Pf 41.644: C (1), retouched by Bronia Wistreich

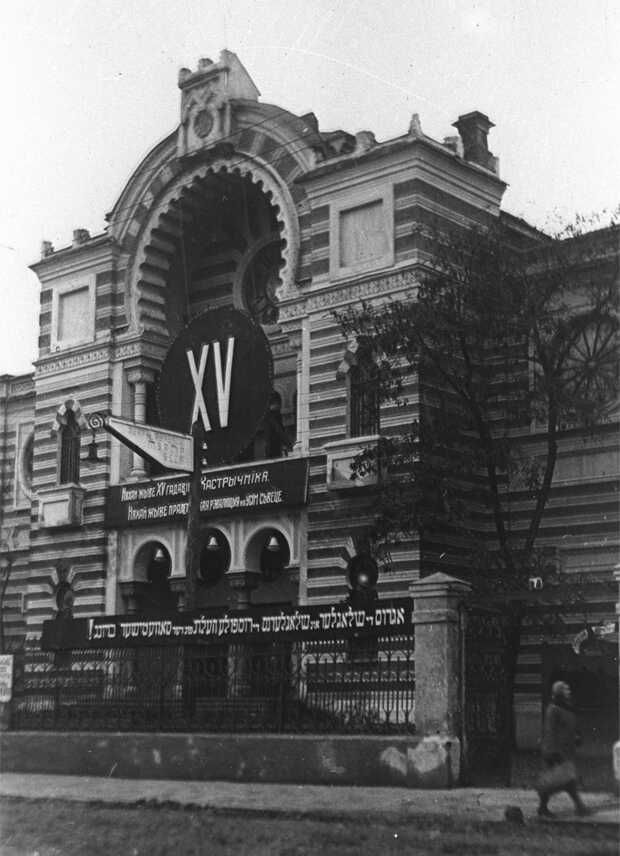

Lili Grün was born on 3 February 1904 in Vienna and was the youngest of four children. Her parents died when she was young. In her youth, Lili Grün was interested in theatre, drama and literature. She performed at a number of theatres, for example at the new theatre of the Socialist Workers’ League in Vienna. In 1931 Lili Grün moved to Berlin. She wrote articles and poems and her work was published in magazines such as Tempo and newspapers including the Berliner Tageblatt and the Prager Tagblatt. She was among the artists who founded the cabaret Die Brücke (“The Bridge”). After time spent living in Prague and Paris, she returned to Vienna in 1933; her first novel was published in the same year.

Because she was Jewish, from 1938 she was banned from publishing her work. She became destitute and suffered from tuberculosis. The authorities forced her to vacate her apartment, probably in 1940. Her final residence was in mass accommodation for Jews in Vienna’s 1st District. On 27 May 1942 she was deported to Minsk on a transport that departed from Vienna’s Aspang railway station. She was murdered in Blagovshchina on 1 June.

Lili Grün was 29 when her first novel, Herz über Bord (“Heart Overboard”), came out. The book was soon translated into Hungarian and Italian. He second novel, Loni in der Kleinstadt (“Loni in the Small Town”), was published by a Swiss publishing house in 1935.

Public domain image

The Romanisches Café on Kurfürstendamm in Berlin was a favourite haunt of writers, journalists, artists and actors. The economic crisis and mass unemployment had a major impact on the artistic community. For Lili Grün, Berlin’s coffee houses were important venues to find new commissions and contacts.

akg-images, Bildnr. 947655

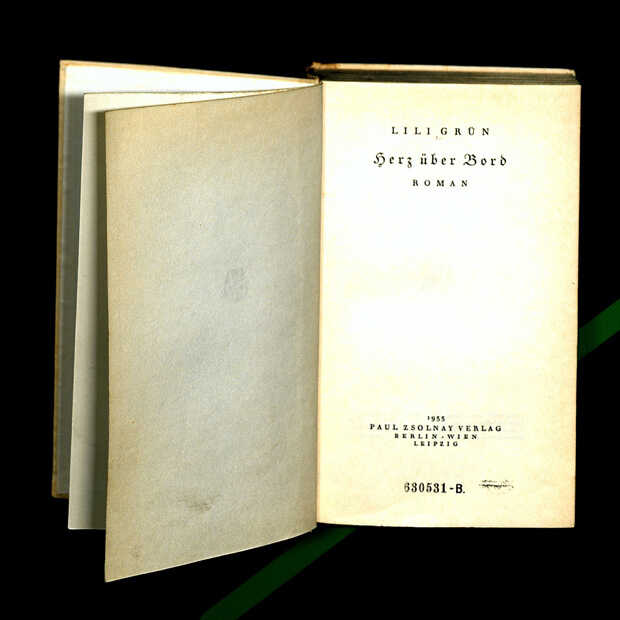

Berlin, 7 May 1931: report from the Vossische Zeitung on a performance by “Lilly” Grün and her “amusing, sentimental poetry”. As a co-founder of the Die Brücke cabaret, she performed alongside actors such as Ernst Busch (1900–1980). She worked in a cake shop by day in order to make a living.

Public domain image

In 1935 Lili Grün spent time in the spa town of Merano in South Tyrol in an attempt to cure her tuberculosis. Her publisher collected donations to fund her stay in a sanatorium; Grün was short of money on account of her publication ban.

Public domain image

Deportees’ luggage being loaded in front of the assembly camp in Kleine Sperlgasse. Lili Grün was deported to Minsk on 27 May 1942. Around 10,000 of the 50,000 Jews living in Vienna shared the same fate. Maly Trostenets was the site with the greatest number of Austrian Jews murdered.

Dokumentationsarchiv des Österreichischen Widerstandes, Vienna

In 2007, a “Stone of Remembrance” was placed outside 4 Heine Street in Vienna in memory of Lili Grün as well as three other Austrian writers: Oswald Levett, Alma Johanna König and Ber Horowitz. They were murdered in 1942 in Maly Trostenets or in Stanislav (Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine).

Stiftung Denkmal

As the result of a citizens’ initiative, in 2009 a square near Augarten Park in Vienna’s 2nd District was named after Lili Grün. At the naming ceremony there was a reading of her reprinted novel Alles ist Jazz (“Everything’s Jazz”).

Stiftung Denkmal

Erich Klibansky

1900–1942

Girls’ class at Jawne School, around 1935

NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln

Erich Klibansky (1900–1942) grew up in an orthodox Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main. He studied history, German and French. In 1928 he married Meta David (1902–1942) from Hamburg. The couple moved to Cologne, where Erich Klibansky became headmaster of Jawne Grammar School in 1929.

Founded in 1919, Jawne was the first Jewish grammar school in the Rhineland region. After Jewish pupils were excluded from German state schools in the 1930s, Jawne School had its highest ever number of pupils. Klibansky tried to prepare his pupils for emigration. After the November pogroms in 1938, he decided to relocate the entire school to Britain. The following year, he arranged for 130 pupils to leave for Britain as part of the Kindertransport rescue effort.

Jawne School was closed down on 1 July 1942. Just a few weeks later, Erich Klibansky was deported to Minsk along with his wife; their three sons Hans-Raphael (1928–1942), Alexander (1931–1942) and Michael (1935–1942); and around 100 pupils from Jawne School. The SS deported a total of 1,164 people from Cologne and the surrounding area on Transport Da 219 on 20 July 1942. After four days, the transport arrived in Minsk. Upon arrival, the deportees were either brought by truck to Blagovshchina, where they were shot at pits dug in advance, or they were murdered in gas vans on the way there.

Erich Klibansky, around 1930. Klibansky was just 29 when he was appointed headmaster of Jawne Grammar School. He sought to strengthen the pupils‘ sense of Jewish identity without isolating themselves in German society.

NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln

Klibansky’s wife Meta with the couple’s three sons Hans-Raphael, Michael and Alexander, around 1936.

NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln

The synagogue of the Orthodox “Adass Jeschurun” community was destroyed in a bombing raid in 1943 and the ruins demolished in the late 1950s.

NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln

In the 1930s St.ApernStreet was a centre of Jewish life. The four-storey building (left) housed the teacher training facility, “Moriah” Primary School and, from 1919, Jawne Grammar School.

NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln

English lesson in the playground of Jawne School, 1938. In order to make life easier for pupils who emigrated, the school placed particular emphasis on language learning: “[Frau Lüthgen, the teacher] taught us to speak French and English really well […] later […] in France I had to go into hiding and no one could tell from my accent that I wasn’t French.” (Anni Adler, former Jawne pupil)

NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln

After the November pogroms in 1938, Jewish organisations arranged the evacuation of around 10,000 Jewish children and teenagers from the German Reich to Britain. Four Kindertransport departures were organised specifically for 130 pupils from Jawne School. Klibansky accompanied these evacuation transports.

Lern- und Gedenkort Jawne, Cologne

Cologne Messe/Deutz railway station, the starting point for the deportation on 20 July 1942. Helmut Lohn, who assisted the synagogue community as the deportation train was prepared for departure, recalls: “I’ll never forget this transport. They were all young, strong people who could look after themselves. This was the one transport where the mood was not overwhelmed by sorrow, where people were one hundred per cent certain: We’ll be back!”

Public domain image

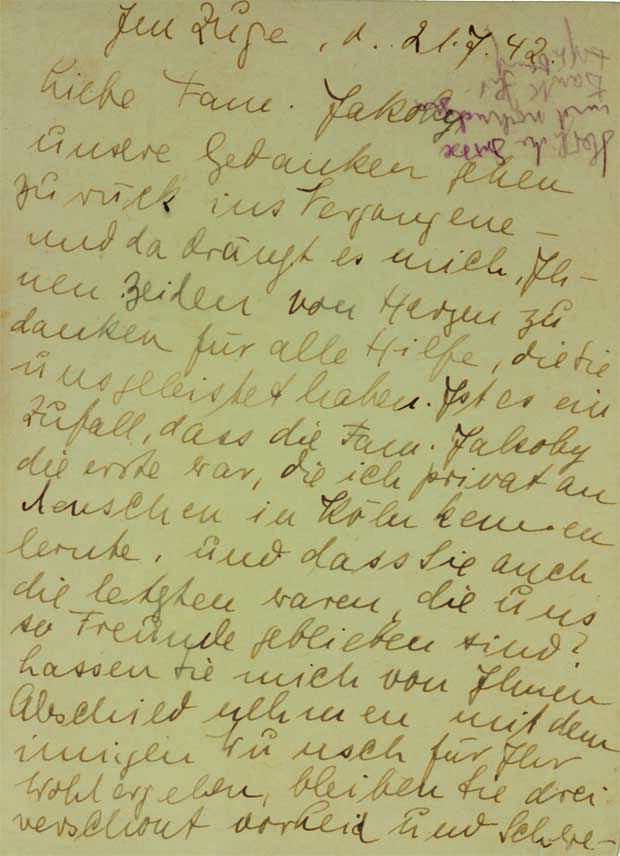

Postcard that Meta Klibansky threw out of the train near Berlin on 21 July 1942. In it she said farewell and thanked the Jakobys, who were friends of the family.

NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln

Erected in 1997, the Löwenbrunnen (Lion Fountain) in front of the former site of Jawne School remembers the 1,100 murdered Jewish children and young people from Cologne, but also the rescue of 130 children organised by Erich Klibansky. The lion sculpture was created by Hermann Gurfinkel (1926–2004), who was one of those rescued. The square is named after Erich Klibansky.

Christian Herrmann

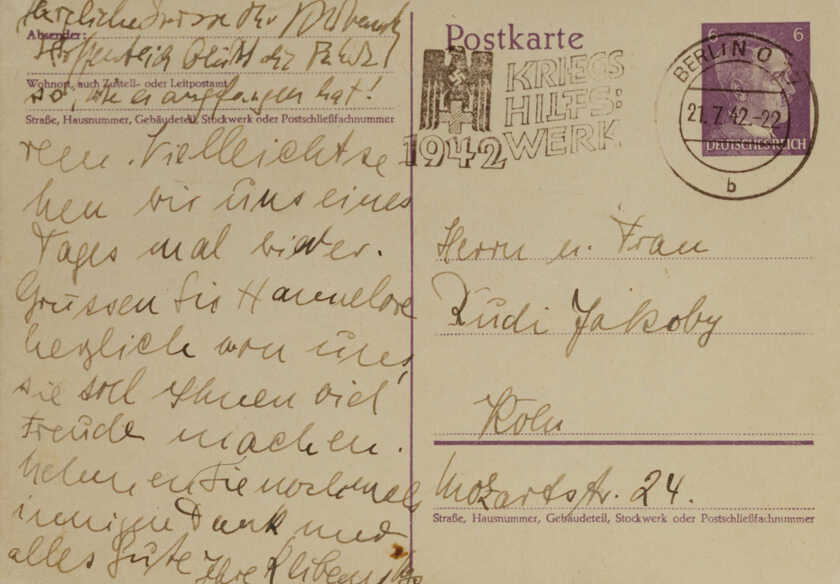

Yevgeniy Klumov

1876–1944

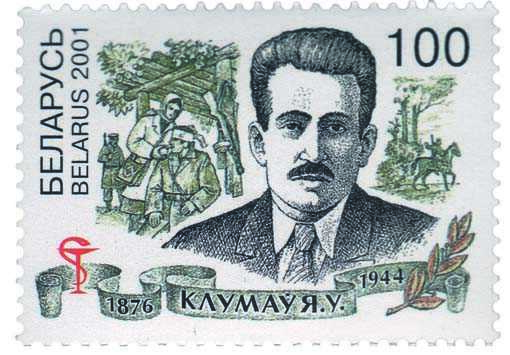

Yevgeniy Klumov, then a student, with his future wife Galina, 1895

Belorusskiy gosudarstvennyy muzey istorii Velikoy Otechestvennoy voyny, Minsk

Yevgeniy Klumov was born in Moscow, where he studied medicine until 1904. In World War One he served as a medical officer in the Russian Army. From the 1920s Klumov headed the gynaecological department of a hospital in Minsk and taught midwifery and gynaecology at the city’s Medical University.

Right from the first few days after the German attack on the Soviet Union, he operated on wounded soldiers in his hospital and had them moved farther away from the front line. In early 1942 Klumov established links with resistance groups in Minsk. He provided them with surgical instruments, medicines and bandages. He treated the wounded and made sure that they were able to get to the partisans. He hid young people in his hospital to protect them from being transported to Germany as forced labour.

In October 1943, Klumov, his wife, and fellow doctors were arrested, interrogated and tortured in the hospital. They were brought to the camp in Shirokaya Street. In February 1944, the SS murdered Klumov and his wife Galina in a gas van on the way to Trostenets. Their corpses were then presumably burnt in Shashkovka.

Yevgeniy Klumov (centre) in a hospital during World War One

Muzey istorii meditsiny, Minsk

Minsk, 1940: Yevgeniy Klumov (first row, second from right) with colleagues from Soviet Hospital No. 1

Muzey istorii meditsiny, Minsk

In Belarus, Klumov is one of the most famous victims of Trostenets. In 1965 he was awarded the posthumous title “Hero of the Soviet Union”. A hospital and a street in Minsk are named after him. This postage stamp was brought out in 2001 to mark the 125th anniversary of his birth.

Belorusskiy gosudarstvennyy muzey istorii Velikoy Otechestvennoy voyny, Minsk

“Towards evening on 8 February 1944, a group of prisoners was brought from Minsk prison to the camp [in Shirokaya Street]. There were many doctors among them, and I recognised Yevgeniy and Galina straight away ... Prof. Klumov looked terrible, he was seriously ill [...] The camp doctor Gurevitch, himself a prisoner, had the Klumovs placed in the sick bay; he gave them his bed [...] I spent five days with them in the sick bay. Yevgeniy told me about the interrogations [...] He felt extremely unwell on account of his diabetes [...] Galina was completely exhausted too; she could barely get out of bed … At around nine in the morning, all of the prisoners had to assemble in the centre of the camp [...] The gas vans drove up a few minutes later.”

From the memoir of the doctor Lyudmila Kashetchkina, a former member of the resistance movement in Minsk

Nikolay Valakhanovich

1917–1989

Nikolay Valakhanovich at a meeting with schoolchildren in the 1980s.

Private collection of the Valakhanovich family

Nikolaj Valakhanovich was a train controller at Negoreloye station, 50 kilometres from Minsk. From April 1943 he compiled reports on the traffic of freight transports and passed these on to contacts within the Soviet intelligence.

On 20 June 1944 – shortly before the liberation of Minsk – Valakhanovich was betrayed and the SD arrested him and a number of other villagers on suspicion of being partisans. He was brought to the prison in Volodarskogo Street in Minsk, where he was tortured. On 29 June the SS then brought him and other prisoners by truck to Maly Trostenets, where they were to be shot. Valakhanovich was taken into a barn in which countless dead bodies were already piled up and he was shot, losing an eye in the process. He lay between the bodies for almost a day and a half before creeping outside – the shootings were still under way – and finding a place to hide. Shortly afterwards the barn was set on fire by the guards.

In the early 1960s the authorities invited him to Moscow to give a witness statement as the Soviet Union was gathering evidence for a trial against members of the SS in Koblenz. Well into old age, Valakhanovich continued to take part in commemorations at Maly Trostenets, where he recounted his experiences to school groups.

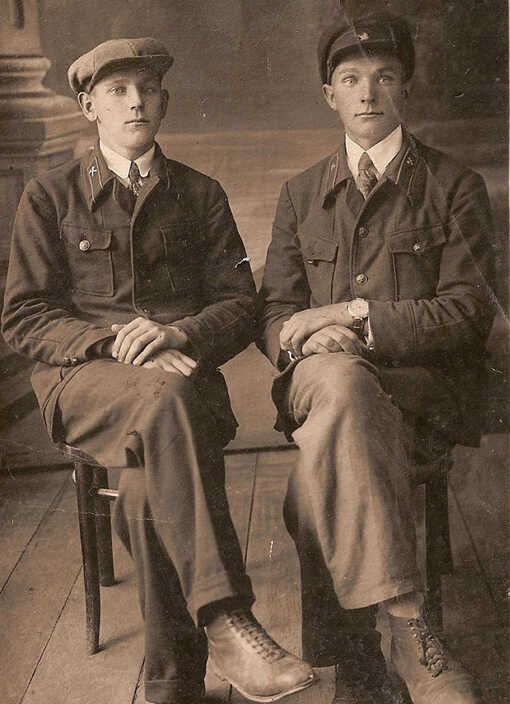

Photo from the pre-war years: Nikolay Valakhanovich (right) and a friend in their railway workers’ uniforms.

Private collection of the Valakhanovich family

Nikolay with his wife Serafima (centre), sister Tamara (left) and brother Alexander, around 1938.

Private collection of the Valakhanovich family

Nikolay Valakhanovich with his wife Serafima (right), daughter Galina (second from left) and son Leonid (second from right) in the 1950s. Galina later said of her father: “He told [his story] to the grandchildren, too. [...] He wanted us children to know what he had experienced. [...] We were to commit it to memory for all time.”

Private collection of the Valakhanovich family

Nikolay Valakhanovich with his wife Serafima (first row, right) and friends in the village of Negoreloje in the 1970s. Nikolaj Valakhanovich lived his whole life in the village.

Private collection of the Valakhanovich family

“And so we were brought to Trostenets, to the camp previously designated for Jews. We did not come across any people there, but there were shreds of clothing, crockery and scraps of bread and potato lying everywhere […] The vehicle drove right up to this barn, or more precisely, up to the door. The first five prisoners had to get out straight away. They entered the barn and shots were heard immediately. [...] Soon it was my turn. [...] I jumped out of the vehicle and went to the barn. There was straw on the floor inside. To the left of the entrance, three or four men from the penal commando were standing in a row. I raised my hands, turned around so that my back was facing the guards and went to stand by the wall; they commanded us to do so using hand gestures. When I turned around and took a step, they opened fire. [...] I soon realised that I was still alive, but I couldn’t understand why […] The shooting went on until late in the evening [...] At around six or seven the following morning, 30 June 1944, the shooting continued. [...] It was just at that time that a vehicle arrived with the next group of prisoners who were condemned to death. The penal commando surrounded the vehicle, the barn door was out of their sight for a short space of time. It was then that I was able to creep out of the barn. [...] I soon managed to get to a field of rye, where I hid and fell asleep.”

Nikolay Valakhanovich

Minsk, 3 July 1962: Nikolay Valakhanovich (foreground, wearing a hat) with his son Leonid (to his right). The group is pictured on the way to lay a wreath at Bolshoi Trostenets on Liberation Day.

Private collection of the Valakhanovich family

Nikolaj Valakhanovich‘s identity card from 1970, which states that he was a former partisan.

Private collection of the Valakhanovich family

“My mother was told that Nikolay had been taken to hospital [...] We had a horse [...] Mother put me in the cart and said, ‘We’re going to see Father.’ [...] All I can remember is that I didn’t recognise the father who was in the hospital. His face was completely bandaged up. I was even afraid to approach him.”

Daughter Galina

Lea and Pinkas Rennert

1896–1942, 1894–1942

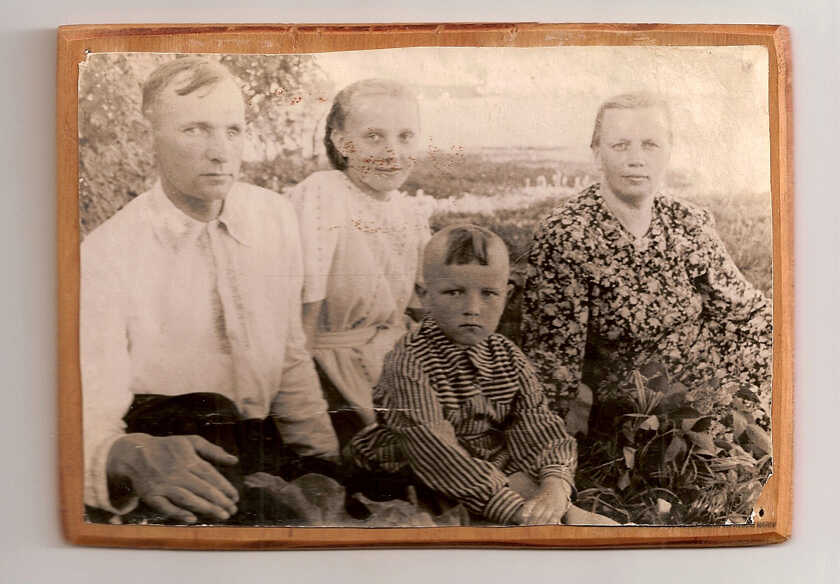

The picture shows Lea Dlugacz Pinkas Rennert, both from the province Bukovina, on their engagement in 1920.

Private collection of the Rennert family

Biography prepared by the Austrian House of History

Lea Dlugacz and Pinkas Rennert were both from the Austrian province of Bukovina, which became part of Romania after World War One. They got engaged in 1920. After their marriage the couple moved to Vienna, where their daughter Silvia was born in 1922 and their son Erwin in 1926. Lea Rennert was a housewife, while Pinkas Rennert worked as a metalware salesman, primarily for the galvanising company “Brunner Verzinkerei” run by the Bablik brothers. After the “Anschluss” (Austria’s annexation to the German Reich), Pinkas Rennert was initially able to continue working within the company as a welder, but then lost this job too on account of his Jewish origins. He was subsequently employed by the Israelite Religious Community. On 31 October 1939 the couple’s two children were able to emigrate to the USA. Lea and Pinkas Rennert’s final residence was in a building in Odeongasse 5/9 designated as collective accommodation for Jews expelled from their homes. On 5 October 1942 they were deported to Maly Trostenets, where they were murdered.

Family photo from October 1938. The Rennerts with their son Erwin (centre) and daughter Silvia (right).

The Rennerts had desperately sought ways for themselves and their children to emigrate. As the couple were from Bukovina, they were subject to the emigration quota for Romanians, which meant that they would be on a waiting list for several years. They finally managed to secure a guarantee of financial security – a so-called affidavit of support – and a visa for the USA for their children. Erwin (1926–2009) and Silvia (married name Rivera, 1922– 2011) left Vienna on 31 October 1939 and travelled via Trieste to the USA.

Private collection of the Rennert family

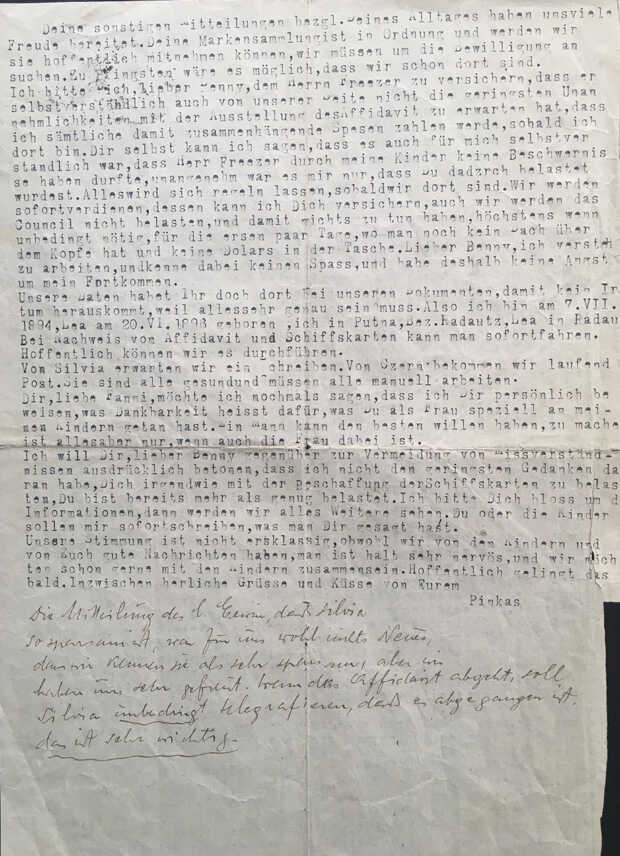

On 7 August 1939 Pinkas Rennert wrote to his cousin Benjamin Dlugacz (Ben Duglas) in New York, asking him to approach Jewish organisations to arrange accommodation for the children, as the Duglas family were not well off themselves. Ben Duglas asked a Mr Freezer from his synagogue congregation to act as guarantor for the affidavit. Mr Freezer agreed, but was not able to look after the children himself. Mr and Mrs Duglas ultimately took both children in.

Private collection of the Rennert family

“What platform [at Vienna’s Südbahnhof station] is the train on? My father and I find our carriage, our compartment, and meet Mr. Weissmann, a friendly stranger; my mother looks at him as if he were our guardian angel. The platform is dimly lit. However, I can see her tears and how she is biting her lip. My father helps us to get our suitcases on board. It reminds me of the luggage in old Perl [a car] and of our trip to Bukovina. My mother also steps briefly into the compartment; she takes a look at our seats as if wanting to see how our futures will turn out. A final hug, she strokes my hair, gives me a kiss, then she has to get off. The train now departs slowly. Silvia and I lean out of the window to wave to our parents. I can still see my mother’s pale, tearstained face and my father holding her arm. They both wave, and then they are gone.”

Erwin Rennert, Der Welt in die Quere. Lebenserinnerungen 1926–1947, Vienna 2000, p. 125

"When the affidavit goes off, Silvia should be sure to telegraph that it has gone off, that is very important."

In their letter of February 17, 1941, to their cousin in New York, Lea and Pinkas Rennert wrote about their hopes of receiving the affidavit soon and made plans for their future. Pinkas Rennert wanted to work as an electric welder, Lea Rennert wanted to make wafers; she already had some machines that she wanted to take with her to the United States. They sent again their exact birth dates so that there would be no mistakes in the affidavit. "... one is just very nervous," Pinkas Rennert noted - two days earlier the first deportation transport had left Vienna for Opole (General Government).

Private family collection Rennert

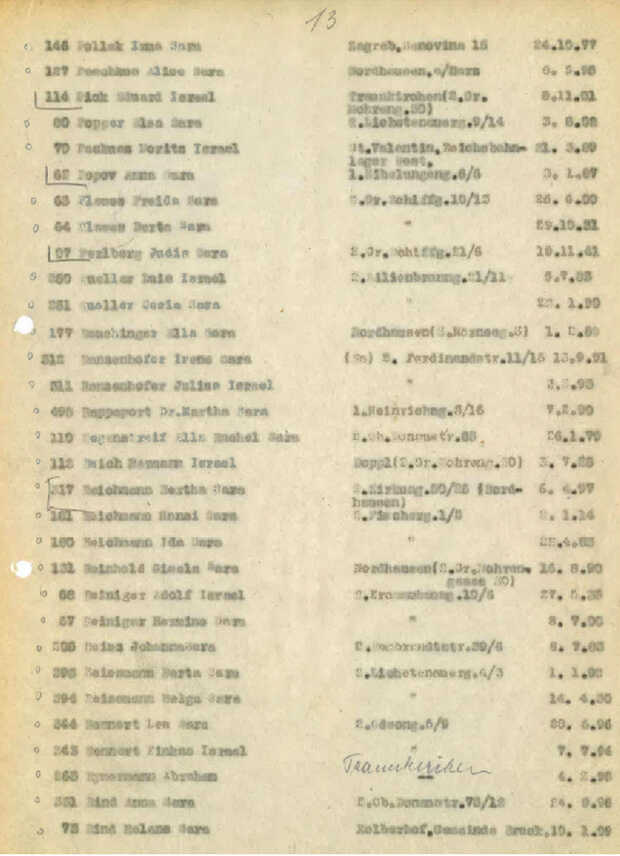

Excerpt from the list for the deportation transport from Vienna’s Aspang station to Minsk/Maly Trostenets on 5 October 1942

Archiv IKG Wien (Leihgabe im VWI), Bestand Wien, A / VIE / IKG / II / DEP / Deportationslisten

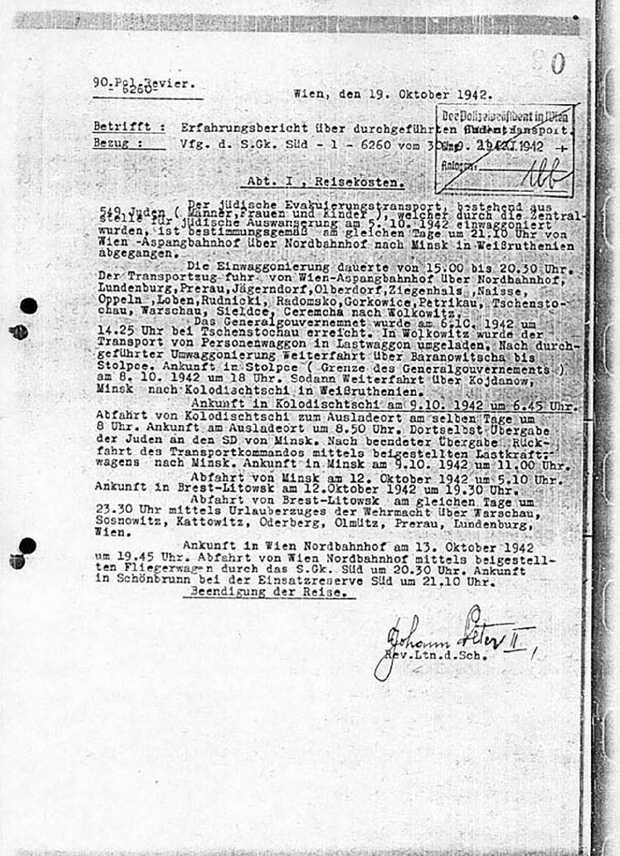

On 19 October 1942 police officer Johann Peter wrote a report on the deportation of 549 Jewish children, women and men on 5 October 1942, among them Lea und Pinkas Rennert. He gave a detailed account of the “boarding” at Aspang station, which took more than 5 hours. He listed the individual stops during the journey and recorded that in Vawkavysk in Belarus the deportees had to get out of the passenger carriages and board cattle wagons. Four days later, on 9 October, the transport arrived in Maly Trostenets, where the Viennese guards handed over the deportees to the SD men.

Yad Vashem Archives, DN/27-3, fol. 27f.; Yad Vashem Archives/DÖW microfilm 58

Fritz (Siegfried) Kneller (1924–1942)

Fritz Kneller, a childhood friend of Erwin Rennert, the son of Lea and Pinkas. On 30 October 1939, the day before Erwin’s departure for the USA, Fritz gave his friend this photo. It was captioned: “To remember your friend Fritz”. Fritz Kneller was deported with his parents Abraham and Pesie Kneller on 27 May 1942 to Maly Trostenets, where he was murdered. Erwin Rennert kept this picture in his photo album for decades.

Private collection of the Rennert family

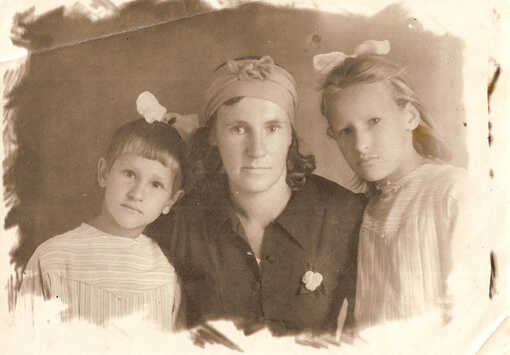

Valentina Shishlo

1936

Valentina Shishlo, at the end of 1940s

Private collection family Shishlo

Valentina Shishlo was born on 10 February 1936 in the village of Beliza, near Shlobin. Her father was an officer in the Red Army and was captured by the Germans in 1941. During the occupation, Valentina and her family lived with her father’s parents in Beliza. In 1943 they were made to live in a stable with locals as well as civilians who had been expelled from Smolensk.

Valentina was eight when the Wehrmacht forcibly evacuated her, her mother Nina Danilova, and her four siblings to the camp near Ozarichi in March 1944. It took several days to get there and the family had to sleep outside at night. Three of Valentina’s younger brothers, Garik, Marat und Boris, perished in the camp. Valentina and her sister Klara survived thanks to their grandmother Varvara, who made a bed for them out of a sheepskin belonging to one of the dead. Nonetheless, Valentina fell ill with typhus and required treatment in a field hospital after liberation.

Valentina’s father Fjodor Danilow, 1941. He was taken prisoner and sent to Dachau concentration camp. He was murdered at the SS shooting site in Hebertshausen.

Private collection of the Shishlo family

Valentina’s mother Nina Danilova, 1937

Private collection of the Shishlo family

Valentina (left) with her mother Nina and sister Klara in the late 1940s.

Private collection of the Shishlo family

“In the morning no one wakes us, the dogs do not bark, there is no sound to be heard. Slowly, everyone raises their heads and anyone who can gets up. There they are, our rescuers. Oh, how many lives it cost, for everyone rushes towards them [the soldiers]. And they shout, ‘Stay there, don’t move a muscle […] they have laid mines throughout the camp’.”

Interview with Valentina Shishlo on 21 December 2018 in Minsk

Valentina Shishlo at Ozarichi Museum in the 1990s. For decades, the qualified technician has been recounting what she experienced and witnessed. Since 2010 she has headed the local association of Ozarichi survivors in Minsk.

Private collection of the Shishlo family

Arthur Harder

1910–1964

Arthur Harder, around 1942

Bundesarchiv (BArch R9361-III/66590)

This text was prepared by Institute for the History of Frankfurt

Arthur Harder was born in 1910 in Frankfurt. From September to November 1943 he headed Sonderkommando 1005-Mitte, which was responsible for removing evidence of the crimes committed in Maly Trostenets. During this period, Harder also participated in the murder of Jewish and Russian prisoners used as forced labour. In November 1943 he carried out the execution of three Jewish prisoners on the orders of the Reich Security Main Office by having them burnt alive.

Most members of the commando recalled Arthur Harder as a tall, powerful man with a loud and brutal demeanour. According to their reports, he would say, “I want to see figures!” (he used the term “figures” (Figuren) to describe the corpses as well as the prisoners) and climb on to the piles of bodies in Blagovshchina forest, and he would beat the forced labourers with whips or cudgels to get them to work faster.

After leaving school (“Volksschule”) and completing a commercial apprenticeship, Arthur Harder initially worked as an employee, but he had already joined the NSDAP and the SA in 1929 and the SS in 1930. From 1938 he worked full time for the Security Service of the Reichsführer SS. In 1942 he was called up for the Waffen-SS and was awarded the rank of Hauptsturmführer in 1944.

In May 1945 Arthur Harder was initially held captive by the British forces, who then handed him over to the Americans. As a member of the SS, he was held in Darmstadt internment camp. On 2 July 1948 a denazification tribunal categorised him as a “minor offender”, put him on probation for two years and issued him with a fine of 200 Reichsmarks.

After returning to live in Frankfurt-Eckenheim, he was a salaried employee at the Krupp vehicles firm. In the 1950s the Frankfurt public prosecutor investigated him for allegedly singing antisemitic songs during a meeting of the “Aid Association of Former SS Members” in a Frankfurt pub. During the investigations, he attacked and seriously injured a prosecution witness and was consequently given a two-month suspended sentence by a Frankfurt court.

In 1963 Koblenz Regional Court found him guilty of the murder of the three Jews whom he had burnt to death in November 1943 and sentenced him to three-and-a-half years in prison. The Federal Supreme Court repealed the sentence. Arthur Harder died on 3 February 1964 in Frankfurt.

“I was a soldier and led a unit and I had no political foresight either and had to believe that we would win the war. I don’t know about any atrocities or crimes committed by the SS, and during the war I didn’t hear about anything like that either.”

Arthur Harder on his role in the Waffen-SS HHStAW, Spruchkammerakte von Arthur Harder (Abt. 520/Da Z Nr. 517804)